Be Seeing You

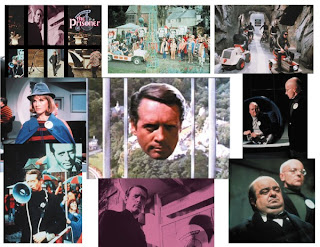

Blogger extraordinaire Jim Emerson is on a tear: after last week's wonderful defense of film criticism, he's back this week with a fantastic multi-media example of it. It's a 12 minute and nineteen second analysis of the opening credits of The Prisoner, the brilliant 1967 British cult series that starred (and was produced by) Patrick McGoohan. The 17 episode series (it ran only one season, giving it the dense, novelesque feel of an amazing miniseries) tells the tale of a spy who resigns from the Secret Service, and is then gassed and taken away to a mysterious "Village," from which he tries to escape over the course of the show. He doesn't know where he is, or why he's there (only that the Village masters demand "information!"), and he even lacks a name, referred to only as "Number Six" (his lead captors-- they generally change with each episode-- call themselves "Number Twos"). Imagine James Bond as filtered through Lewis Carroll and Andre Breton: it's less a thriller (although it's plenty exciting) than a surreal discourse on the nature of the self, the elasticity of genre, and what we mean when we discuss the stakes of knowledge (in many ways, it predicts the questions that will dominate poststructuralist criticism for decades). And it looks incredibly cool, a Swingin' London day-glo aesthetic wrapped around a Rousseau-like vision of natural utopia whose ideologies get turned inside out, and made insidious.

All of this demands close analysis, and in Emerson, The Prisoner has found an apt narrator: choosing to structure his critique as a film, he runs the opening credits twice, stopping and starting, freeze-framing on images that catch his eye, layering other music over the imagery in order to call attention to items or ideas in the frame, and to make theoretical links out from the text. All of this might seem unbearably pretentious if Emerson himself weren't so witty (it's a trip in itself to finally hear Emerson's voice after all these years of reading his prose), weren't so intent on sharing his geeky enthusiasm in such a fun, generous way. It would make a fantastic teaching tool, or example for class presentations. Describing one moment in the credits (as McGoohan walks down a shadowy hallway), Emerson says, "It's kind of like the flicker of the movies themselves," something we could also say of his poetic, cinephiliac analysis.

Comments